In Julio Cortázar’s “Islands at Noon,” a flight attendant becomes inexplicably obsessed with a Greek island. Every time his plane flies over this stretch of the sea at noon, he leans against the window, captivated by the shimmering island below. Though it’s just a fleeting moment, it gives meaning to his entire job.

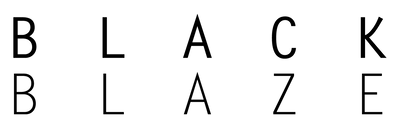

Like the flight attendant’s fascination with the island at noon, certain places carry an almost magical allure—sometimes just their name or their distant, unreachable quality sparks an irresistible urge to visit, to explore, to become infatuated for no clear reason. For travelers to Sydney, names like Bondi or La Perouse may sound exotic yet remain unfamiliar, not easily evoking an immediate connection. But Palm Beach is different. It doesn’t remind you of Indigenous heritage or maritime explorers, but it ignites a desire to set out without hesitation.

There is no foreign charm in its pronunciation, nor any historical resonance. Palm Beach, with its straightforward name, paints a simple picture: you think of palm trees, you think of beaches. Two uncomplicated images that, left to the imagination, evoke sunlight, sea breezes, and endless summer.

An hour’s drive from Sydney, I always arrive at Palm Beach near noon. To me, Palm Beach is such an “island at noon,” with its glistening sea making it impossible to look far into the distance. Amidst the sparkling waves, you may catch sight of migrating whales from Antarctica, frolicking as they make their way north. They travel as part of their life journey, breeding and growing along the way. Visitors often stand on the cliffs, watching these ocean wanderers leap out of the water and move slowly onward, as if they were drifting islands themselves.

The Tasman Sea, where whales swim, and the serene waters of Pittwater are divided by the narrow peninsula of Palm Beach. From a high vantage point between the two, it’s the perfect spot to take it all in. From an even higher view, Palm Beach looks like the tail of a whale just before it dives into the ocean, or a palm tree swaying in the wind—a singular wonder amidst the sea. I often see planes above Palm Beach, and I imagine pilots slowing down just a little as they pass, savoring the view, holding onto the charm of Palm Beach as a personal, quiet secret.

Palm Beach holds a different kind of sentiment for Sydneysiders. It’s one of the filming locations for Australia’s iconic soap opera, *Home and Away*, where it’s known as Summer Bay—a setting for family drama, love, and heartbreak. Since it began airing in 1988, the fictional Summer Bay has become a portrayal of Australian life on screen, lending Palm Beach a familiar, homely feel. The show’s title was translated as “Gathering and Parting,” capturing the bittersweet flow of family stories. Whenever I come to Palm Beach, I think of these words and reflect on how, no matter whether a story takes place at home or far away, it’s always a kind of family narrative. Now, three years after moving to Australia, it’s only through experiencing my own moments of “gathering and parting” that I realize just how fragile the sense of comfort in building a ‘home away from home’ can be.

In Cortázar’s story, the writer describes the flight attendant finally “landing” on the island: “He let himself be carried by the currents to the mouth of a cave before turning around and swimming back to the sea, floating on his back and, in a gesture of reconciliation, accepting everything and deciding his future.”

To “let oneself…and then”—this is the poetic moment that exists in every ordinary life. Its importance is not apparent at the time but eventually shapes the direction of one’s story. Letting the plane drift, letting the current carry him—only after the stubborn courage of letting go can there be the satisfaction of “then,” the peace that comes from accepting everything and embracing the decided future. Unlike the flight attendant, a 29-year-old ground crew member from Seattle once stole a plane one summer evening to see the stranded whales. He ultimately crashed on a deserted island, but not before looping through the sky like an acrobat, as if to put an end to his unrealized dreams. In Cortázar’s story, the crash brings the attendant to his long-desired island—perhaps a disaster that was just imagined while he leaned against the window. This ambiguity is what makes the story so intriguing—the potential disaster might have been nothing more than a fleeting scare, yet it still opens up the possibility of another imagined life.

*Home and Away* still resonates—the meaning of “away” remains, and the length of life can indeed be measured in meters. Tarkovsky once imagined his ideal work to be capturing every second of a person’s life on millions of meters of film, eventually editing it down to a feature-length movie. Even by the standards of a great film, life is only about 25,000 meters of film. Daily life can be more mundane than any soap opera, its drama not even matching the day’s news. The most memorable news I recently heard was of that young man from Seattle. In some ways, his story mirrors the ending of “Islands at Noon.” Fate itself is inherently literary, hinting at paths laid out long before.

You stand at the headland, a fire lit at the end of the narrow land. The crackling flames reflect the Barrenjoey Lighthouse looming behind you. Sea breezes send sparks into the night, mingling with scent, drifting across the evening air. And so, at midnight, you once again meet the brightness of noon. This is Black Blaze’s Beach Bonfire—a moment recorded in scent.

Whether an island, a pod of whales, or any other fascinating element in life, they are all “cave entrances” in the flow of daily life—places where we linger, marvel at something new, and seek reconciliation with the world and ourselves.

Palm Beach seems destined for the noon hour, for bright sunshine and carefree emotions, where you can wander between the bushes and beach until twilight draws near, at ease and content. At night, Palm Beach has a different beauty: lighthouses attempting to communicate with whales’ songs, loneliness stretching from the cliffs into the deep sea, waves and whale calls echoing around the headland.